This article does not discuss any specific station, brand of equipment, or individual failed project. The technical phenomena and engineering issues mentioned are derived from recurring engineering experiences with DRM (Digital Radio Mondiale) systems in medium-wave and short-wave transmission chains in recent years.

It must be stated upfront: these issues do not mean that existing medium-wave/short-wave systems are unusable. Rather, they signify that if existing analog AM-era engineering assumptions are directly used to carry OFDM digital signals, the risk will no longer be gradual but structural.

This article is written against the backdrop of China's medium-wave and short-wave broadcasting approaching a phase of systematic digital transformation. Before proceeding with equipment tendering, system integration, and field implementation, it is necessary to thoroughly review some engineering constraints that may seem like details but are actually critical to success.

In the analog AM era, the core objectives of the engineering system were carrier stability and controllable modulation depth. The system allowed for a certain degree of non-linearity, phase drift, and bandwidth asymmetry; as long as the listening experience was acceptable, the broadcast was considered "successful."

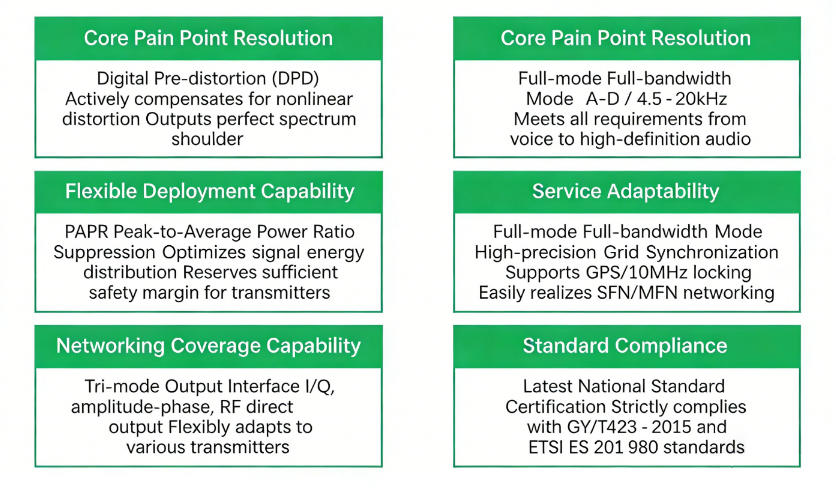

The underlying logic of DRM is completely different. It is a digital system based on OFDM and the orthogonality of multiple sub-carriers. Its success depends on:

· Synchronization accuracy of amplitude and phase

· Controllability of the spectrum edges

· And the consistency of the entire transmission chain in both time and frequency domains.

This means: Many practices considered "standard engineering habits" in the AM era will directly become sources of distortion in DRM.

The first hard constraint imposed by DRM concerns the connection method between the modulator and the final power amplifier.

In the Magnitude/RF-Phase structure of DRM:

· The modulator output must be directly fed into the final power amplifier via DC coupling.

· Any modulation structure based on transformer-coupled Class B operation will introduce uncontrollable low-frequency distortion and DC drift.

This is not a matter of "technical route debate," but rather signal structure incompatibility. Once the DC bias cannot be precisely matched:

· The amplitude distribution of OFDM sub-carriers will experience systematic offset.

· Out-of-band emissions will increase, and this increase may not always be immediately visible on a spectrum analyzer.

Engineering Case Analysis ①: "Spectrum Compliant, But Reception Performance Persistently Abnormal"

In a certain medium-wave DRM pilot project, the transmitter fully met the spectrum mask requirements in laboratory tests. However, after actual broadcasting began:

· The receiver SNR showed abnormal fluctuations.

· At the same location, analog AM reception was normal, but DRM demodulation frequently lost lock.

The root cause was eventually traced back: The problem was not in the RF stage, but rather an AC-coupling structure existed in the modulator output stage, causing the DC bias to drift slowly under different load conditions. This issue was difficult to detect in single-point tests but accumulated gradually during prolonged broadcasting.

In the DRM system, the Magnitude and RF-Phase signals are not independent. There is a fixed relative delay relationship between them that must be strictly controlled.

This means:

· Even if the amplitude and phase paths individually appear "high-performing,"

· Any inconsistency in the fixed delay between them will introduce systematic EVM degradation.

This issue held almost no engineering significance in the AM era, but in DRM, it is part of the demodulation threshold.

The audio path in DRM is essentially the baseband I/Q signal path. Its bandwidth requirement is directly determined by the signal structure:

· Typically requires ≥ 3.5 times the DRM signal bandwidth.

· In practice, a flat audio path above 40 kHz is a basic prerequisite.

This leads to a series of chain reactions:

· All band-limiting filters used in the AM era to "optimize audio quality" must be removed.

· The sampling frequency of PDM/PSM modulators must satisfy the Nyquist criterion.

· The output filter must not only have expanded bandwidth but also maintain flat group delay.

Engineering Case Analysis ②: "Frequency Response Compliant, But Group Delay Ruins Everything"

During a transformation at a certain station, only bandwidth expansion was performed on the audio link. The amplitude-frequency test was fully compliant, but DRM demodulation performance remained unstable. The problem was finally pinpointed to: The original AM-era audio equalization network introduced severe group delay ripple, causing phase rotation at OFDM symbol boundaries. This is an "invisible" problem, but DRM will mercilessly amplify it.

The Peak-to-Average Power Ratio (PAPR) of DRM signals typically falls within the 8–10 dB range. This means:

· A DRM average power of 10 kW

· May require the transmitter to have a peak linear capability of 20 kW or even higher.

Two common misjudgments are easy to given:

1. Equating AM carrier power directly with DRM average power.

2. Underestimating the sustained high-duty-cycle thermal load of the digital signal.

Unlike AM:

· DRM has no "quiet passages."

· Power amplifier devices and the power supply system operate under high thermal stress for extended periods.

Engineering Case Analysis ③: "Power Not Exceeded, But Tube Lifespan Plummets"

In an old medium-wave transmitter operating in DRM mode, all parameters were initially normal, but the failure rate of power amplifier devices increased significantly within months. The ultimate finding was:

· The cooling system was designed for the average modulation depth of AM.

· Under the continuous load of DRM, the junction temperature remained near its limit for prolonged periods.

Such issues will not trigger immediate alarms, but they will inevitably manifest within the maintenance cycle.

In medium-wave systems, antennas are often tuned to:

· Present a purely resistive load at the center frequency.

· Exhibit a rapidly increasing reactive impedance component away from the center frequency.

What DRM requires is symmetric, linear, and predictable impedance variation. Common engineering recommendations are:

· ±10 kHz: VSWR ≤ 1.1

· ±5 kHz: VSWR ≤ 1.05

This is not just a "specification requirement," but an empirical conclusion for ensuring consistent radiation of OFDM sub-carriers.

In multi-mast systems (e.g., Yagi, Four Posters):

· Coupling effects can increase the Q factor.

· Bandwidth issues are more easily amplified.

Short-wave systems are relatively more lenient, but not entirely free of constraints.

OFDM's sensitivity to phase noise is far higher than AM's. If the local oscillator source has excessive phase noise:

· Sub-carrier orthogonality is compromised.

· Demodulation performance rapidly degrades in low SNR scenarios.

Engineering practice recommends:

· Locking the entire system to a GPS-disciplined 10 MHz reference source.

· Avoiding the use of old, standalone crystal oscillators with un-evaluated phase noise performance.

This is not about "pursuing high-end configuration," but about avoiding fundamental mismatch.

DRM will not "tolerantly adapt" to existing medium-wave/short-wave systems. It will faithfully expose problems that were previously masked by analog broadcasting.

Before launching large-scale transformations:

· Clarifying these issues

· Is far more efficient than writing summary reports after failures occur.

If this article appears calm, it is because these problems are serious enough without needing exaggeration.